‘We Have Generational Trauma’ Armenians at John Jay Reflect on Their Everlasting Fears of Continued Genocide

May 24, 2021

In September of 2020, Armenia and Azerbaijan re-engaged in a war over disputed territory, Nagorno-Karabakh, referred to as Artsakh for Armenians. It remained an unresolved conflict for years, prompting new attacks on several occasions, but tensions peaked last year.

The most recent conflict led Armenians to cite the Azerbaijani aggressions as potential acts of continued genocide as they were aided by Turkey, the country responsible for the Armenian Genocide in 1915.

Turkey has acknowledged that killings did occur in 1915. However, they argue Armenians hyperbolized the extent of the lives taken, denying any notion of the events being genocidal.

The tensions were only further exacerbated when Azerbaijan, a near self-proclaimed extension of Turkey, continued its war with Armenia, which in this occurrence, left Armenians with pressing fears they were facing an existential threat.

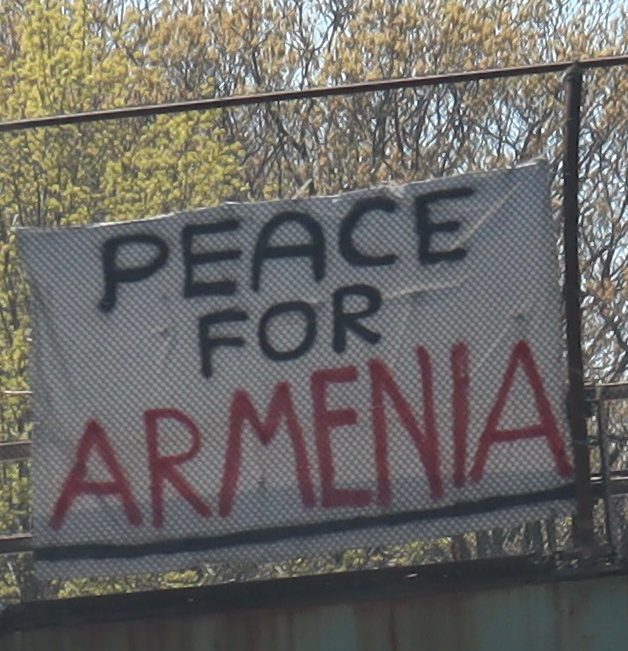

Less than a year later, Armenians continue to worry history will repeat itself. The side-effects of the continued attacks against its people appeared as a potential continuation of 1915. Although, even now, many are still hoping for their voices to be heard and ancestors to be remembered.

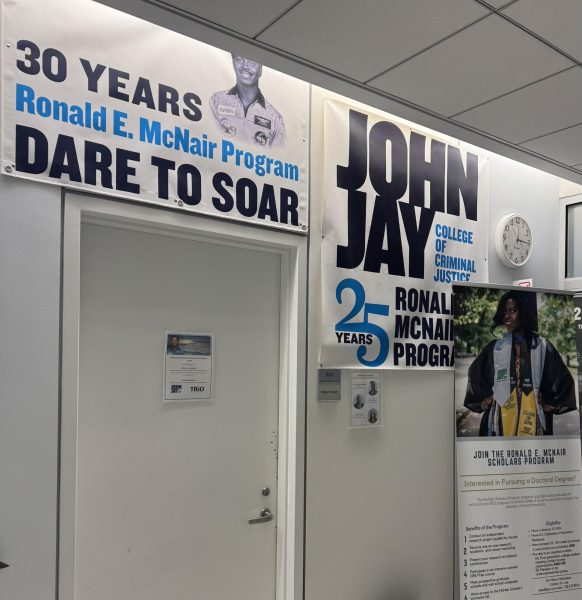

Like most Armenians, the scant John Jay Armenian community felt a generational agony and fear when the regional conflict resurfaced.

Armenians have continuously struggled to find hope that their traumas would come to an end.

In various ways, the world has not adequately recognized the atrocities the Armenian population endured over a century ago — the mass killing and displacement of Armenians was supremely underreported in 1915 — and has subsequently been underreported ever since.

Adolf Hitler, when rallying up Nazi Germany, stated, “who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?”

Given the lack of acknowledgment of the genocide, students and faculty from the Caucasus region are generally the most knowledgeable of the events — leaving most of the other individuals in the institution with limited knowledge of what happened in 1915.

Carlos Once, a John Jay student who does not have Caucasus region heritage, offered a limited understanding of the Armenian Genocide or the recent conflict with Azerbaijan yet considered it a misfortune.

“It’s a topic that hasn’t been covered in the schools I’ve attended but should be,” Once said. “It’s an important discussion but the only information I see is through social media.”

Since and during the events of last year, social media appeared to be the only platform for Armenians to speak out on the conflict as it went relatively unnoticed in the press.

Most notably, Kim Kardashian had spoken out through her Instagram asking for support for Armenia. She is half-Armenian through her late father, Rob Kardashian.

Still, the world’s silence remained, and the lack of attention gave Armenians credence that Azerbaijan and Turkey may cleanse them at any moment.

Dr. Gohar Petrossian was one of the many who felt her country could face extinction at any moment.

Dr. Petrossian was born and raised in Gyumri, Armenia, the countries second most populated city. She later moved to America in 1999 after receiving a scholarship to attend an American university. She then became a professor in Criminal Justice at John Jay College, lecturing at the college since 2013.

While she was not a witness to either 1915, or the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict of 2020, she is a first-generation descendant of a genocide survivor through her mother and lost friends and classmates this past year in the war over the disputed territory.

She fears Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has dreams of exterminating Armenia. She implores anything but silence to be the requisite response.

“Remembering the Armenian Genocide means paying tribute to the victims,” she said. “It is also a constant reminder of the existential challenge our nation faces in light of the complex geopolitical ambitions of the region and a way to keep us alert.”

Remembering the many lives lost in 1915 protects Armenians from further loss, according to Petrossian. As long as there is denial and a lack of recognition from the world, Armenians are at risk.

“Should we let our guard down, we may be easily wiped out of the surface of the earth, just like many other nations before us,” she added.

Petrossian also sees Artsakh as the final page in Armenian history. Losing Artsakh would be losing Armenia. She feels Artsakh is essential in avoiding what Turkey and Azerbaijan plan for Armenians.

Without it, the 2.9 million Armenians residing in the homeland would be all but lost because nobody would stop them.

“Inevitably so, our fears are real and justifiable,” Petrossian said. “If the world remains silent about this conflict, it will not be long before Turkey attempts another cleansing of the ‘remnants of the sword’ in Armenia. Who will stop them?”

Armenians have a sincere and genuine concern with Turkey accepting little blame or refusing to offer any restitution for its crimes, hitting an apex last year when Azerbaijan re-engaged in a war with Armenians.

The worry extends to the 7 million Armenians who live in the Armenian diaspora, the larger population of Armenians than those residing in the homeland.

Sergei Khatchatourian, a John Jay student, is a proud member of the Armenian diaspora. He, like many others, could not express the magnitude of his sadness and grief for all the loss of Armenian life.

He could recall learning about the genocide as a tragic loss of beautiful lives, a reason to lack trust in humanity, and a reason to bond in honor of being an Armenian.

Khatchatourian rivaled the world’s lack of regard for what happened to his people, his ancestors, and those like him. He wants answers for why the world still cannot hear the voices of millions of Armenians.

“Not again. There’s no way,” he said. “I cried because I knew deep down, we were going to face this alone. No one was going to help, just like in 1915.”

In several ways, Armenia was alone again. The country of less than 3 million was facing Azerbaijan and Turkey who have a combined 90 million people.

More than a mere century after the Armenian Genocide, the world did not chime in again.

Fellow John Jay College student and member of the Armenian diaspora, Susan Yegoryan, could not stress how important it is for the world to step in and save what is left of Armenia, her people.

“Turkey has taken so much from us,” she said. “The biggest fear to me is that we’re going to have nothing left.”

She felt remembering the fallen was of utmost importance, and every calendar year, on April 24th, Armenians gather to remember 1915. Although this year, United States President Joe Biden stood with them in solidarity, recognizing the events of 1915 as genocide.

He was the first United States president to use genocide to describe the atrocities of 1915 officially. However, in 1981, Ronald Reagan informally used the term genocide in a statement to the press. Roughly every other president had side-stepped making any statement on the issue.

For most Armenians, the statement was not enough, too late, and the bare minimum. They still fear for their lives and cannot erase the past, but only fear reliving it.

“Nobody wants to hear our voices,” Yegoryan said. “We have generational trauma, that is what is going on right now.”

elizabeth • May 24, 2021 at 7:58 pm

no ones homeland should be taken away from them or have the risk of being taken away from them. it’s their home